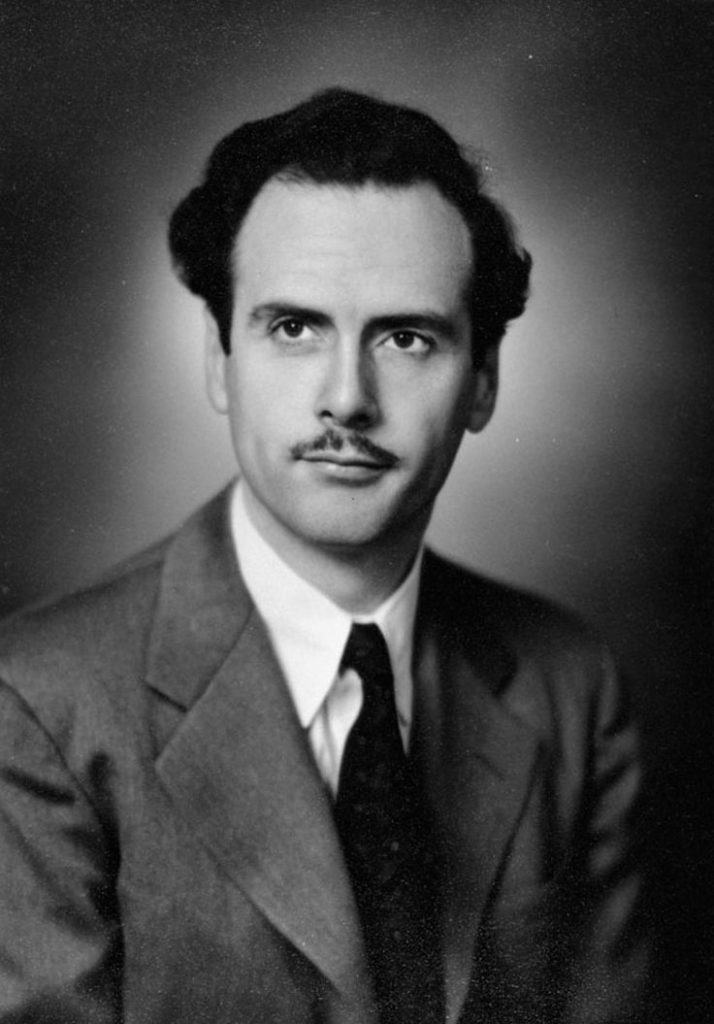

If you’re a member of the marketing world, you’ve most likely heard the aphorism “the medium is the message.” This truism is a staple proverb of marketing and digital communications. But did you know that that classic phrase was coined by a Catholic? Marshall McLuhan, who coined the phrase, was a leading media scholar and a devout Catholic convert.

Brett Robinson, of Notre Dame’s McGrath Institute for Church Life, wrote a lovely profile on McLuhan during Summer 2018. This past summer, Aaron Riches of Benedictine College in Kansas wrote an incisive essay meditating on the liturgical aspects of McLuhan’s work.

Riches’ essay prompted me to think further about what role the internet and digital communications play in the New Evangelization—or, really, in evangelization, period. The core unit of Christian evangelization is the local Eucharistic community—the parish. The parish gathers together to do the liturgy together, to offer themselves up to God through Christ, and to be transformed into Christ for the world.

His essay raises particularly provocative points about the nature of technology. Riches draws on some of the ideas about the human being and technology from the twentieth-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Heidegger believed that the human person—you and me, as we walk around in our daily lives—reveals the truth of being in the world around us.

While the finer points of phenomenology might not appear to have a place on a digital communications blog, Heidegger’s ideas remain salient for any conscientious, creative communications professional.

Heidegger’s image of the human being as a “revealer of truth” is a pretty easy idea for Christians to latch onto. We are made in the image and likeness of the one true creator God—the foundation of all truth.

“Being” by its very nature is an “unconcealment,” continues Heidegger; it makes some hidden truth manifest for everyone to see. If we think about who Christ is, we see that Jesus is the being par excellence, as he reveals God himself—not just an image and likeness, like us—into the world.

Besides their own “being,” Heidegger notes an additional way that humans disclose truth, i.e., making truth visible in the world: what the Greeks called poiesis, that is, art: poetry, music, painting, drama. Art reveals the truth about what it means to be a human being.

Just so, argues Heidegger, technology, from the Greek word techne, can reveal the mystery of Being—of God and God’s truth—into the world. Technology, then, has a pretty lofty calling: not only to reveal the truth, but to be a way of revealing God—capital-T Truth.

In a lot of our news cycle, we encounter the failings of the internet: social media platforms that distort truth, news sites that become echo chambers, or those web communities that even actively foster hate. We read about the failings of tech companies. We experience data breaches or loss of privacy.

Given the internet’s many publicized shortcomings, is it really a space that can reveal truth? Can Heidegger’s lofty ideas about technology apply to contemporary digital communications?

In his book The Medium and the Light: Reflections on Religion, Marshall McLuhan says that each new medium—television, phone, radio, internet—opens up a new way of existing in the world. It opens up new experiences and new ways of thinking for each human being who encounters this new medium.

When Jesus told the disciples to bring the Gospel to the “ends of the earth” (Mk 16:15), he expressed the hunger of the Divine Love to encounter every person in every place. Jesus’ words also contain in them a perennial truth: there is no place the Christian Gospel doesn’t belong; there isn’t a single place on this earth Jesus can’t belong.

There isn’t a single place we can’t bring Christ, there isn’t any place, no matter how large, how small or how strange that Christ doesn’t desire to be a part of. The internet, as a new medium of communication, opens up a new way for human beings to interact. It opens up a new medium for Christ to make himself known.

Pope Francis has called the internet a “gift from God” to be used wisely. The internet can promote authentic relationships with our fellow humans. But McLuhan suggests that it can be even more than that, it can be another place where we can learn more about God and God’s love for us.

One of DeSales’ priority tech initiatives is to develop parish websites. How do parish websites, I wonder, work as a way of bringing people to the truth, revealing the God of truth and life to others?

As we work to build parish website software, we constantly remember that our goal is not to keep eyeballs glued to the digital page, but rather to drive visitors to in-person encounters: with parish staff members, with the community of the parish, with the Body of Christ. The website is the parish’s digital front door, as it were, an inviting space that serves to attract new members, educate about the Catholic Church, or welcome in strangers looking for a place to go to Mass.

In his essay, Riches claims that the purest form of media, where the medium is the message entirely, is the Catholic liturgy. In the liturgy, the Sacramental Sign of Christ’s body and blood isn’t just a symbol, it really is Christ. The liturgy reveals the truth of who God is: the God who is the bread of life, the life of the world, who sustains us, and who transforms us into bread for others.

The Eucharistic liturgy is the most powerful means of evangelizing. In the Eucharist, we encounter the perfect message: Christ. As the source and summit of our Catholic faith, the Eucharist is the clearest form of communication with the God of love. The liturgy offers a much stronger connection than any other medium—digital or otherwise—can offer.

Update: Check out Molly Gettinger, Communications/Branding Manager for the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend, reflecting on communion and connection on the internet for the Grotto Network.